An Explanation of the Monty Hall Problem

Explanation (from Andrew)

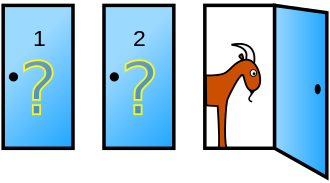

I provide the explanation here and the problem description below because the explanation is my work, but I have copied and pasted the description from Wikipedia. It is important to note that one of the greatest mathematicians (Erdos) was not convinced until he was shown a Monte Carlo simulation of the problem. It wasn’t the case that Erdos did not understand the explanations by enumeration and so on. It was surely the case that Erdos was simply skeptical of them. However, for the average curious about this problem, enumerating is sufficient to induce belief. Following is a figure I drew to show the enumeration.

Description (from wikipedia)

The Monty Hall problem is a brain teaser, in the form of a probability puzzle, loosely based on the American television game show Let’s Make a Deal and named after its original host, Monty Hall. The problem was originally posed (and solved) in a letter by Steve Selvin to the American Statistician in 1975.[1][2] It became famous as a question from reader Craig F. Whitaker’s letter quoted in Marilyn vos Savant’s “Ask Marilyn” column in Parade magazine in 1990:[3]

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

Vos Savant’s response was that the contestant should switch to the other door.[3] Under the standard assumptions, the switching strategy has a 2 / 3 probability of winning the car, while the strategy that remains with the initial choice has only a 1 / 3 probability.

When the player first makes their choice, there is a 2 / 3 chance that the car is behind one of the doors not chosen. This probability does not change after the host reveals a goat behind one of the unchosen doors. When the host provides information about the 2 unchosen doors (revealing that one of them does not have the car behind it), the 2 / 3 chance of the car being behind one of the unchosen doors rests on the unchosen and unrevealed door, as opposed to the 1 / 3 chance of the car being behind the door the contestant chose initially.

The given probabilities depend on specific assumptions about how the host and contestant choose their doors. A key insight is that, under these standard conditions, there is more information about doors 2 and 3 than was available at the beginning of the game when door 1 was chosen by the player: the host’s deliberate action adds value to the door he did not choose to eliminate, but not to the one chosen by the contestant originally. Another insight is that switching doors is a different action from choosing between the two remaining doors at random, as the first action uses the previous information and the latter does not. Other possible behaviors of the host than the one described can reveal different additional information, or none at all, and yield different probabilities.

Many readers of vos Savant’s column refused to believe switching is beneficial and rejected her explanation. After the problem appeared in Parade, approximately 10,000 readers, including nearly 1,000 with PhDs, wrote to the magazine, most of them calling vos Savant wrong.[4] Even when given explanations, simulations, and formal mathematical proofs, many people still did not accept that switching is the best strategy.[5] Paul Erdős, one of the most prolific mathematicians in history, remained unconvinced until he was shown a computer simulation demonstrating vos Savant’s predicted result.[6]

The problem is a paradox of the veridical type, because the solution is so counterintuitive it can seem absurd but is nevertheless demonstrably true. The Monty Hall problem is mathematically closely related to the earlier Three Prisoners problem and to the much older Bertrand’s box paradox.